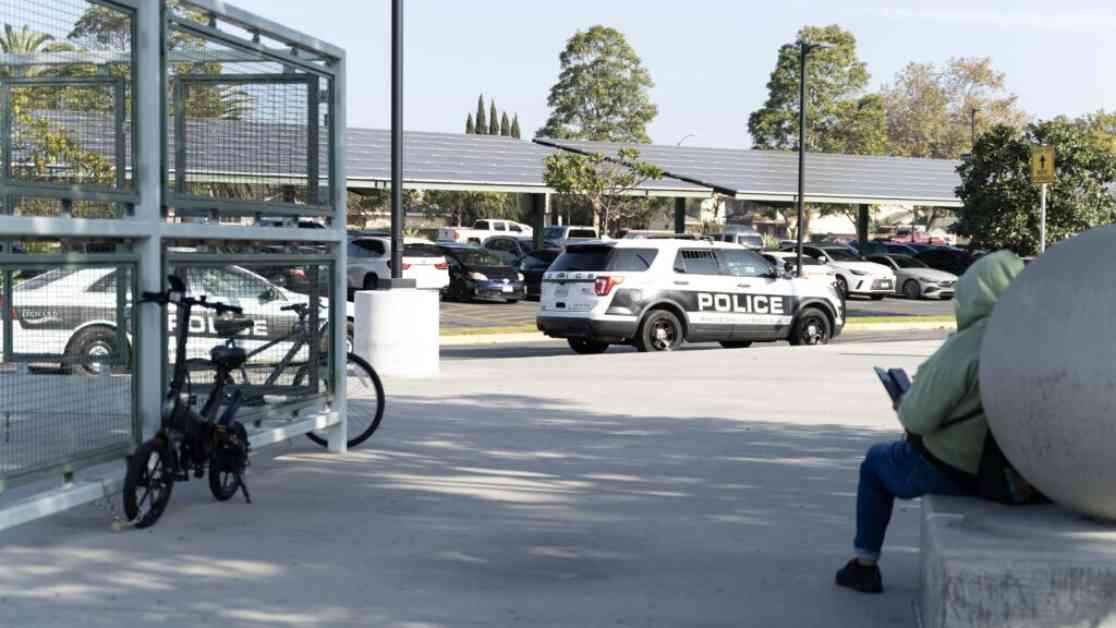

California schools are shelling out millions of dollars each year to have cops on campus, according to an investigation by EdSource. The money, originally intended for education, is now going towards policing, and school boards aren’t keeping a close eye on it.

Not all districts have resource officers, with some calling 911 for help and others having their own police departments. Many contract with cities and counties for officers from local law enforcement agencies.

Without statewide data on school policing in California, EdSource obtained contracts from 89 districts, revealing that school boards often approve these agreements without much public discussion. Contracts worth hundreds of thousands of dollars are bundled into routine votes, raising concerns about transparency.

Most contracts do not require annual evaluations, despite federal recommendations. In districts where reporting is mandated, police agencies often fail to submit reports, and school officials rarely follow up.

The lack of guidance from the state Education Department leaves districts to navigate policing contracts on their own. This lack of oversight has resulted in districts spending at least $85 million on resource officers, with potentially higher costs due to unspecified charges in some contracts.

The hefty price tags for resource officers, which can surpass the salaries of mid-career teachers, have raised eyebrows among experts. Retired Judge LaDoris Cordell criticized cities and counties for turning school safety into a profit-making venture, arguing that resource officers should be provided at no charge.

In some districts, resource officers cost over a million dollars annually. Elk Grove Unified School District, for instance, pays $8.5 million over three years for deputies from the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office, including expenses for patrol cars and cellphones.

The issue of “double taxation” arises in districts where schools foot the bill for officers already paid for by local governments. Oxnard Union High School District, for example, covers 75% of Oxnard’s police officers’ salaries, leading to concerns about taxpayers paying twice for the same service.

While some districts pass measures to fund resource officers through sales taxes, others face criticism for inefficient spending. The National Association of School Resource Officers notes that cost-sharing arrangements vary widely across the country, with some districts bearing the full brunt of officers’ salaries.

Despite concerns over the necessity and effectiveness of resource officers, a majority of parents support having armed police on campus. The contracts reviewed by EdSource rarely address the role of armed officers in student safety, focusing instead on general security measures.

Annual assessments of resource officer programs are recommended by the U.S. Justice Department to ensure their effectiveness. However, many districts fail to request or receive crucial data on officer activities, even when required by contract.

The sloppy practices of some school boards, such as delayed ratification of contracts and lack of transparency in voting, have raised questions about the oversight of school policing. Concerns about misstated contract costs and overdue approvals highlight the need for improved accountability and transparency in school policing practices.

Overall, the investigation by EdSource sheds light on the complex and often overlooked issue of school policing in California, revealing a system in need of greater scrutiny and oversight.